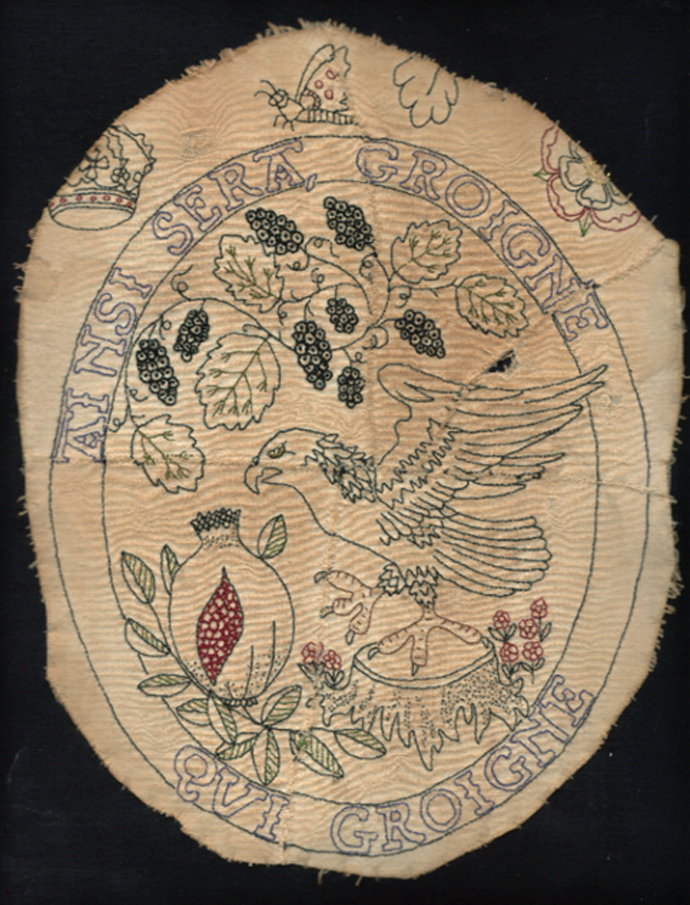

Elizabeth Boleyns Embroidery c.1530

On loan from a private collection.

Catalogue notes by Suky Best

Linen embroidered in silk with metallic thread detail. Back (Holbein) stitch. Contemporary restoration worked in unbleached cotton.

This remarkable fragment of embroidery probably the central part of a cupboard cloth (1) has been attributed to Elizabeth Boleyn. Thought to have been made in the winter of 1529/30, in the heady days proceeding her daughter Anne Bolyen being married to King Henry VIII and crowned queen of England. It satirically depicts a falcon with Tudor roses (the badge of Anne Boleyn) pecking at a pomegranate (the badge of Katherine of Aragon Henry VIII first wife)(2). The French, ainsi sera, groinge qui groinge (that’s the way its going to be however much people grumble) written around the central design, was said to be Anne’s motto during this period.

Elizabeth and her daughter didn’t have a particularly close relationship and perhaps this embroidery was an attempt on the mother’s part to ingratiate herself with her daughter to whom she owed the families newly exhaulted wealth and position in society. Elizabeth although of royal decent from Edward I (3) was relatively impoverished.

When Anne Boleyn and her brother George Boleyn Viscount of Rochford were arrested on (most probably false) charges of treason May 2 1536 it seemed very clear to everyone involved that they were going to be found guilty. Anyone close to the family was thrown into fear for their own safety and survival. One of the main prosecution witnesses at their trial was George’s wife, Jane Rochford. It was not unheard of for associated family members to be arrested and imprisoned. A design such as this would have been evidence of treason as it would have been a reminder of Henry VIII’s bewitchment by Anne.

George and Anne Boleyn were tried and executed within three weeks of their arrest. During these weeks one imagines that Elizabeth decides to destroy objects that could be classed as treasonable, in panic and shock at the probable fate of two of her three children. Already all evidence of the queen is being obliterated from the royal places. Elizabeth cuts out the central part of the cupboard cloth into many pieces and hides them behind panelling at Greenwich Place, where she was living; sadly none of the rest of the cloth survives. There the embroidery remained until the extensive restoration of Greenwich palace undertaken by Charles II in the mid-seventeenth century. It was found by a craftsman working in the building and sold to someone newly indulging in monastic memorabilia after the English civil war.

Incredibly this fragment survived although sadly not in one piece. It has been part of a private collection ever since.

(1) A cupboard cloth was used to create a stage on which precious vessels could be displayed; they could also be used in bedchambers and often showed scenes of an intimate nature.

(2) Embroidery technique is characteristic of amateur blackwork, this technique was used on both furnishings and dress. The design may have been drawn for Elizabeth directly onto the cloth my a court artisan, The illustration copies one found in a music book held in the British library.

(3)Elizabeth Boleyne was also the grandmother of Queen Elizabeth I.

The real story of this piece:

Elizabeth Bolynes Emboridery is totally fictitious and was made for an art exhibition Exhumed at the Museum of Garden History 2003. The museum occupies a former church, St Marys-at- Lambeth, on the river thames very close to Lambeth Palace. In former times the church was important, and many people of note were buried in the churchyard. As one of the selected artists for this exhibition, I was invited to make a piece of work about someone who was buried in the churchyard and I chose Elizabeth Bolyne, Ann Bolynes mother. I researched the stitches and style at the Victoria and Albert Museum London (V&A ) and copied designs and drawings of the time and sewed it over about 6 weeks. The accompanying text to the embroidery is totally fictional with a few historical facts thrown in. Once the embroidery was complete, I cut it up, and aged it, then I sewed it back together to make evidence of a convincing story about its loss, and rediscovery. The textile restoration team at the V&A museum advised me on ways that they would display a real piece of fabric of that date.

I presented the work as if it was a real piece, the context of it being in a contemporary art show ought to have given enough clues as to it authenticity.

Over the years I have been asked to lend it to real museums, and have refused, after telling people that it isn’t real.